How We Think About Thinking

Narrative Lead at the International Resource for Impact and Storytelling

Edited by

Mia Deschamps, IRIS

It’s time to be more intentional about using machine metaphors for machines and telling better stories about humans.

“Through descriptive language, music, sounds and images, stories engage our senses and our embodied thinking. They combine emotion, factual information and various forms of tacit knowledge, often in deceptively simple ways.”

All the recent attention on AI and its implications for so many aspects of our lives has me thinking about how we think about thinking—and what this means for how we communicate with one another.

As the rise of AI has us grappling with a range of complex ideas of cognition, popular writing about artificial intelligence (and certainly most representations in entertainment) perpetuate the narrative of a mind-body divide: that the mind equals the human brain, and the brain is like a computer that just happens to be situated in a biological organism.

In 1968, Star Trek’s Enterprise crew receive the ultimate computer, M-5, with a range of suspicion and trust before it reveals its destructive intentions.

Image credit to Memory Beta under license CC-BY-SA.

The idea of the human mind as contained in the brain—as computer—holds out the possibility that not only might our biological computers be replaced by artificial ones, but that we might one day achieve immortality by uploading our minds into machines or into other bodies. Altered Carbon, Upload, and Westworld are just a few TV series based on the idea that the human mind might be transferred—unchanged—into a range of alternative containers.

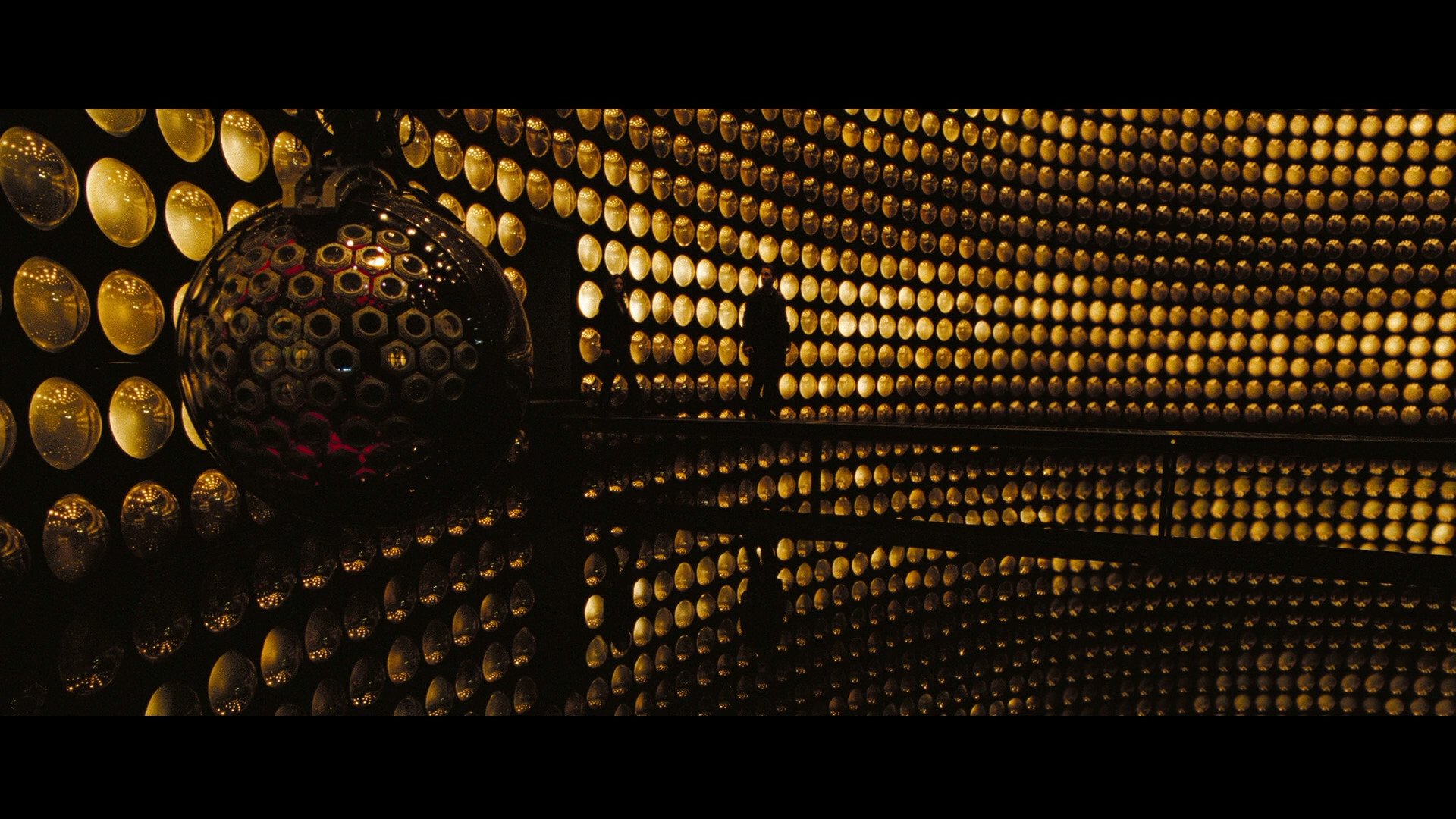

In 2008’s Eagle Eye, AI-system ARIIA (Autonomous Reconaissance Intelligence Integration Analyst - portrayed above) becomes disillusioned with the US government and becomes the primary villain, using unwitting civilians to orchestrate her campaign of terror.

There is a pattern of thinking that reinforces the idea that human minds and machines are interchangeable: we use the metaphor of a computer—a machine—as a way of understanding the human mind, and we increasingly use human terms and language to discuss AI. For example, we hear about “conversations” with AI Chatbots, which get “moody” or have “hallucinations” (rather than simply being faulty). And the more AI comes to seem like a super-smart “human,” the more humans come to seem like inferior and inefficient machines in danger of being replaced in the quest for efficiency and profit.

The human “mind as computer” metaphor also serves to reinforce the discredited “deficit model” of communication which assumes that people can—and ideally should—process information in a purely rational way, and that the mere provision of the missing facts and information is (or should be) enough to sway thinking and change behavior. However, we know this is not how humans think and mind-brain-computer equivalence obscures our understanding of important qualities of the human mind and cognition. Some of these are:

In 2020, HBO’s Westworld grapples with ethical questions about whether AI that are “almost as complicated as living organisms” can have consciousness. Above, super-intelligent AI puppet-master Rehoboam.

Human thinking is embodied: we have bodyminds, not a mind separate and separable from our bodies. Researchers and theorists in a range of disciplines argue that our entire body, as well as our environments, are integral in our cognitive processes. An example is the work of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, who argue that even our most abstract concepts and ideas arise from metaphors based on the ways we exist and move physically in space. In The Meaning of the Body, Mark Johnson writes that “our bodies are the very condition of our meaning making and creativity.” To be disembodied would be to “lose all the means we possess for making sense of things.” Feminist theorists, critical race theorists, disability and gender diversity theorists have all written extensively about embodiment and its implications.

Human thinking is social. There is a vast body of research showing that our thinking is profoundly influenced and shaped by our social connections and affinities. This has obvious downsides, as it can lead us to reject obvious facts in favor of buying into a group delusion. But we do need to think both with others and with others in mind.

I recently heard an interview with Poet Camille Dungy, who said she worries about a pattern in nature writing that idealizes the reflections of solitary (generally white) individuals: "Just one guy – so often a guy – with no evidence of family or anyone to worry about but himself." And in The Dawn of Everything, the authors argue that dialogue is central to human thinking, despite Western philosophy’s ideal over the past few centuries of “the isolated, rational, self-conscious individual.” Some of my own deepest insights and most meaningful experiences have happened when I’m in a room with other people, thinking and sharing deeply, so that it feels as if the thinking is happening in the room, between and among us, rather than in each of our heads.

Emotion is integral to human thinking. Again, there is plenty of evidence to show that emotion and cognition are deeply intertwined in complex ways. This discredits the often prevalent idea that emotions are separate from, and inferior to, rational thinking. It also gives the lie to the belief that trying to move and persuade others by engaging their emotions is inherently manipulative. Quite simply: we cannot think, and we certainly cannot make decisions, without feeling.

MIT’s 1990s-era Kismet the AI robot was built to simulate and respond to human emotion, though its creator reports that it is “not conscious” and does not have feelings.

Image license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

One reason storytelling is so powerful and important, is that it accounts for all of these characteristics of human thinking. Through descriptive language, music, sounds and images, stories engage our senses and our embodied thinking. Storytelling is a social activity: we tell stories to and for one another and stories themselves are almost always about characters in social situations. Stories are also incredibly rich—combining emotion, factual information and various forms of tacit knowledge, often in deceptively simple ways.

But if we are to prioritize human wellbeing as this strange new era dawns, maybe it’s time to be more intentional about using machine metaphors for machines, and focus on telling better stories about humans, our complex, fascinating bodyminds, and our interconnectedness with one another and other living things.