AI’s future (and ours) is up to all of us

“Nothing is inevitable unless we decide it is.”

By Brett Davidson

Narrative Field-Building Lead at the International Resource

for Impact and Storytelling

Edited by

Mia Deschamps

Special Thanks to

Raúl Cruz

The recent unveiling of AI-generated ‘actor’ Tilly Norwood has reignited criticism and alarm over the encroachment of AI in entertainment – but debate and discussion over the appropriate and ethical use of AI tools in both fiction and non-fiction storytelling has been raging for a while.

IRIS’s Founder and Director Cara Mertes and I recently participated in a panel on this topic at the Camden International Film Festival. Our joint message was that—as we grapple with the possibilities, dangers and ethical questions connected to the role of AI in storytelling—we should not lose sight of one important fact: what we think of as ‘AI’ itself is based on a set of stories we’ve been told. As Karen Hao points out powerfully in her book Empire of AI, narrative is at the core of AI – what we understand it to be, what we think it’s for, and what we believe it holds for our future.

At the heart of it all is a narrative of inevitability: AI is the future; AI will take our jobs; Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—conscious AI—is coming, like it or not. This narrative of inevitability is shaping funding, policy, research agendas and all sorts of other decisions.

However, this is just a narrative, just a story. And it’s a story we don’t have to accept. What this pervasive narrative of inevitability does is make us forget that we—we humans—get to decide. Do we want AI? If so, what kind of AI do we want? Do we want it to take people’s jobs? Do we want it to destroy our environment? If not, let’s decide differently.

As much as we are being forced to grapple with how this new technology helps or hinders us from telling stories – or even changes the nature of storytelling itself – it is important to understand that narrative comes before the technology, not after it. Narrative shapes the kind of technology we desire and work to create, it shapes what we seek to do with that technology, and it shapes who gets to control and benefit from it.

This in turn means that storytellers should be central in deciding the future of AI – in deciding our future. In fact, storytellers already play a leading role: after all, as Hao makes clear, Sam Altman, who heads OpenAI, is primarily a storyteller, a salesman, not a tech expert. The problem is that his story—and those of others like him in Silicon Valley—has so far been able to drown out most others.

What happens with AI, and with us, will depend—depends right now—on the outcome of a contest of narratives. It is a contest we urgently need to engage in, with a more diverse range of storytellers and artists at the leading edge.

It is with all of this in mind that IRIS is engaging in an exciting body of work, spurred by Luminate, exploring the connections between narrative, AI and democracy. Right now, there are three parts to this work.

First, if we want to dive into the narrative contest over the future of AI, we need to understand the narrative terrain: what are the predominant narratives, and whose interests are they serving? To this end, IRIS project manager and public interest technologist Di Luong is developing an annotated bibliography of existing research work into the plethora of cultural narratives about AI, and how those narratives in turn impact our understanding of ourselves as humans, about politics and democracy, the nature of truth and even of the past and future.

From the resources included in the bibliography, we see a number of themes emerging, many of them quite troubling:

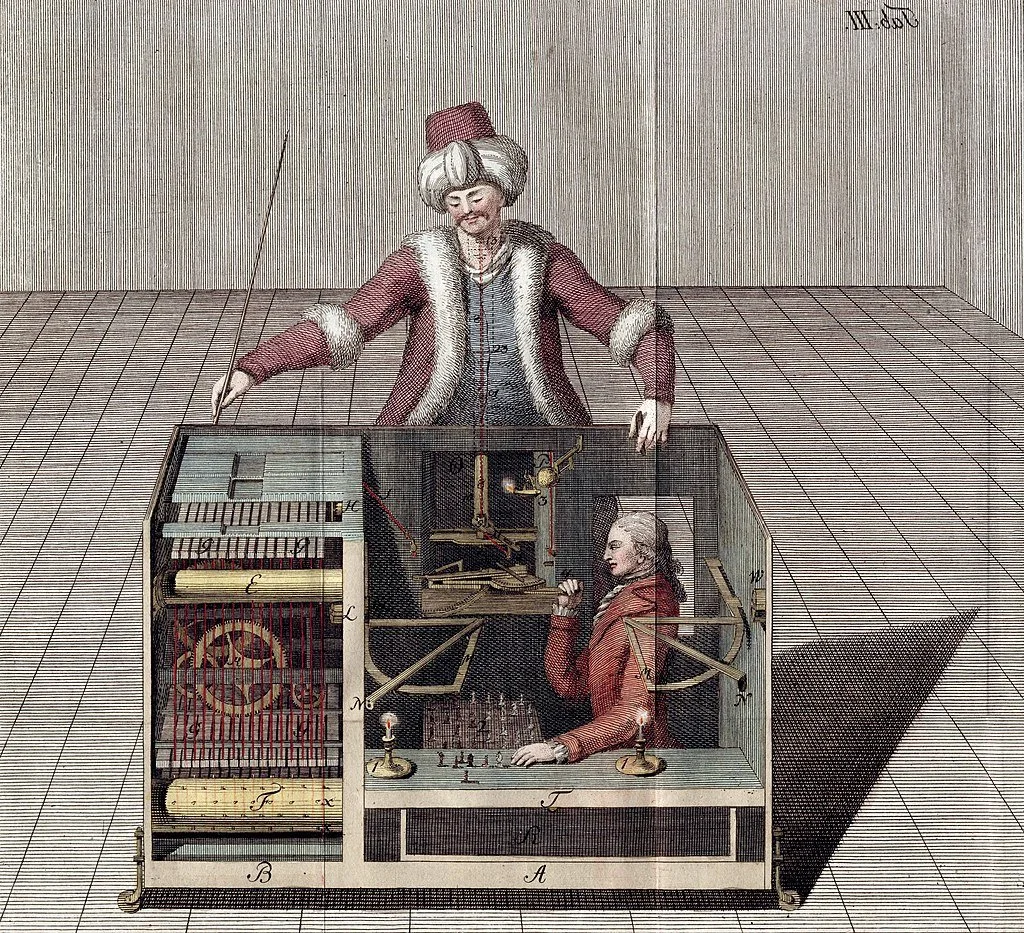

Surveillance and Control: From intelligent machines which guard a knight’s pavilion in the 12th century poem Perceval, to the present-day deployment of automation and biometric tools in surveillance and border control, we see AI being used to monitor and restrict the movement of particular groups and enforce conservative morality.

Rights and Belonging: Ideas about intelligence—deeply rooted in sexism, racism and eugenics—have long been used to determine who gets to be a citizen: who has rights. If, as we are being told, AI is (or soon will be) more intelligent than humans, that opens up a deeply troubling and problematic debate about the rights of machines with respect to humans (and we are already seeing this start to happen as in the case of a recent article in the Guardian asking wither AI’s can suffer, or the granting of citizenship to a robot named Sophia in Saudi Arabia, in 2017.

Technosolutionism: Mark Andreesen’s Techno-Optimist Manifesto, and the idea that Elon Musk’s DOGE team can ‘fix’ government with some code, are perhaps the most extreme versions of this but the idea that technology can fix everything is also deeply embedded in Western culture. As Ruha Benjamin, Joy Buolamwini and many others have pointed out, however, technology is not neutral and tends to replicate and deepen existing biases and inequalities while masking the fact that it is doing so.

Male creators, male protagonists: The predominant forms of AI have been created and programmed overwhelmingly by male creators and used in the service of mostly male protagonists. The vision of an ideal future that we are being sold is one dreamed up by a tiny group of extremely rich, mostly white, men in Silicon Valley, and it's one they alone are likely to benefit from.

Upending conceptions of truth, and time: In a fascinating paper, Nishant Shah argues that in a world run by AI, by social media and algorithms, ideas about the past and future become reversed. Conventionally we have viewed the past as fixed and the future as uncertain. But now platform-driven misinformation and AI hallucination is erasing history, while predictive algorithms turn the future into a realm of probability rather than possibility. At the same time, ‘truth’—once determined by time, when something has already happened in the past—is becoming a matter of quantity, dependent on virality (if enough people believe it, it must be true).

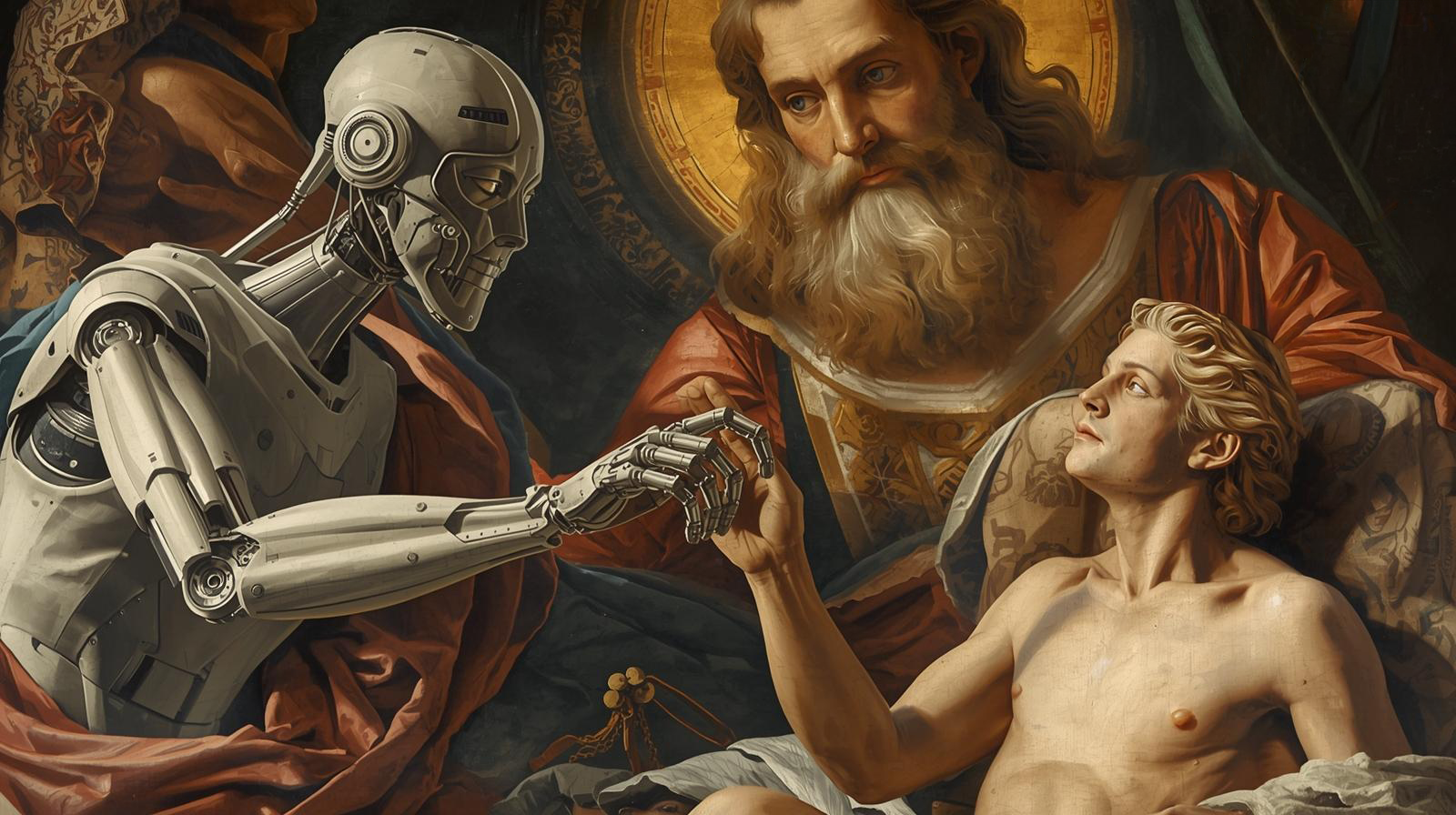

Aside from the last bullet, many of these themes are deeply embedded in Western culture via art, fiction and entertainment from ancient Greece to the present, as the book: AI Narratives: A History of Imaginative Thinking about Intelligent Machines makes clear (I reviewed the book in an earlier IRIS blog). To challenge these and other dominant narratives is going to take significant resources focused on supporting and foregrounding a wide diversity of voices and stories, both new ones and those, with just as ancient a lineage, which have been silenced, marginalized or erased. In their book, Imagining AI, editors Stephen Cave and Kanta Dihal feature several examples – such as the art of Raúl Cruz, whose depictions of intelligent machines are rooted in the ‘ancestral aesthetics of Mesoamerican cultures’, or Jason Edward Lewis’s description of future imaginaries for AI ‘founded in Indigenous perspectives’.

Futurist aesthetics and science fiction combined with Mesoamerican Indian art directly influence RACRUFI’s work, in which he mixes the past and the present with unpredictable futures.

Photo credit: Raúl Cruz / RACRUFI, Illustrator / Fine Artist

Secondly, we need to better understand how stories about AI impact democracy: what kind of stories are detrimental to democracy and what kind are likely to support or strengthen it? Our work in this area begins with a paper by Daniel Stanley of the Future Narratives Lab, in which he looks at deep trends in our democracy that have helped produce—and may be reinforced by—the form of AI we are now seeing. Stanley explores how extractive AI is the product and reflection of exploitative, anti-political logics that have come to dominate our democratic life in recent decades, how they undermine the possibility of collective political identity and action, and where the opportunities might lie for building new forms of power to oppose them.

Finally, we are aiming to understand how organizations and activists are engaging in the contest right now: how are people doing pro-democracy, pro-social justice work in the context of AI and the information environment as it currently exists and what lessons can we learn from that?

To that end we have commissioned 10 case studies of pro-democracy and social justice work in the age of AI and surveillance capitalism. We are already seeing themes of action and hope emerge across these cases, such as:

ways people are building community and organizing in the context of algorithm-driven surveillance and control;

the emergence of new forms of journalism and fact-based storytelling, with media organizations emerging as civic actors;

the reinterpretation of popular culture in support of mobilization and resistance; and

co-opting of AI tools for research to inform narrative strategy.

This work is still ongoing, but we have already learned a lot and aim to publish all of this to inform civic-minded storytellers and to begin equipping and mobilizing narrative alternatives to the dominant story about AI. Nothing is inevitable unless we decide it is. It is through democracy that we, the people, should control and decide the future of AI, not the other way around.